A Remembrance of Mosquitos Past

By

Leo de Natale

There have been so many movies where a nostalgic protagonist sits someplace and time travels into the past. The scene is displayed as waves drifting back and forth, then and now. Memories ebb and flow. The Rosebud scene in Citizen Kane. Childhood play in a playground. Awkward teenage years. A first love and a first heartbreak. The thoughts become a movie reel and suddenly the memories accelerate with speed. While sitting in a train seat the scenery moves so fast it becomes a blur.

The train jolts to an abrupt halt and you sit pondering where time has gone. Suddenly you are an older person and your life has become a repository of events, some important, others trivial or forgettable.

And so it happened to me the other day. I was walking to my car after completing a new endeavor: yoga classes for beginners aka “Seniors”. The studio was located in downtown Waltham, Massachusetts, a very familiar area.

I sat in the car and that wave of nostalgia engulfed me. On these streets, I drove to and from a college summertime job that, in retrospect, had a seminal influence. As important, it was a blast.

Muscle memory navigated me through a route in the city’s blue collar neighborhoods. The majority of businesses were auto repair shops, sheet metal businesses and warehouses. Along the streets were rundown triple-decker homes that housed yet another generation of immigrant workers and their families. Little was different in this section of the city.

At the end of one of main streets was a narrow, semi-paved road, Fern Street. I turned left , took a sharp right and there it was: a garage and free standing office: The East Middlesex & Suffolk County Mosquito Control Project. The building, once yellow, was now painted white. Otherwise, its appearance hadn’t changed. I had returned to the 1960’s. The memory was still a reality.

On a whim, I knocked on a closed door. A grey-bearded, middle-aged man appeared. He was dressed in a cotton tee shirt, Bermuda shorts and sandals.

“Hi, I’m Brian Farless,” he said in a friendly tone. “How can I help you?”

“Well, you might say I’m Morley’s ghost,” I replied chuckling. “I worked here in the 1960’s. I was one of the Project’s Hell’s Angels.”

“You’re kidding!,” Farless exclaimed. “I knew about the Project’s motorcycles but never saw one.”

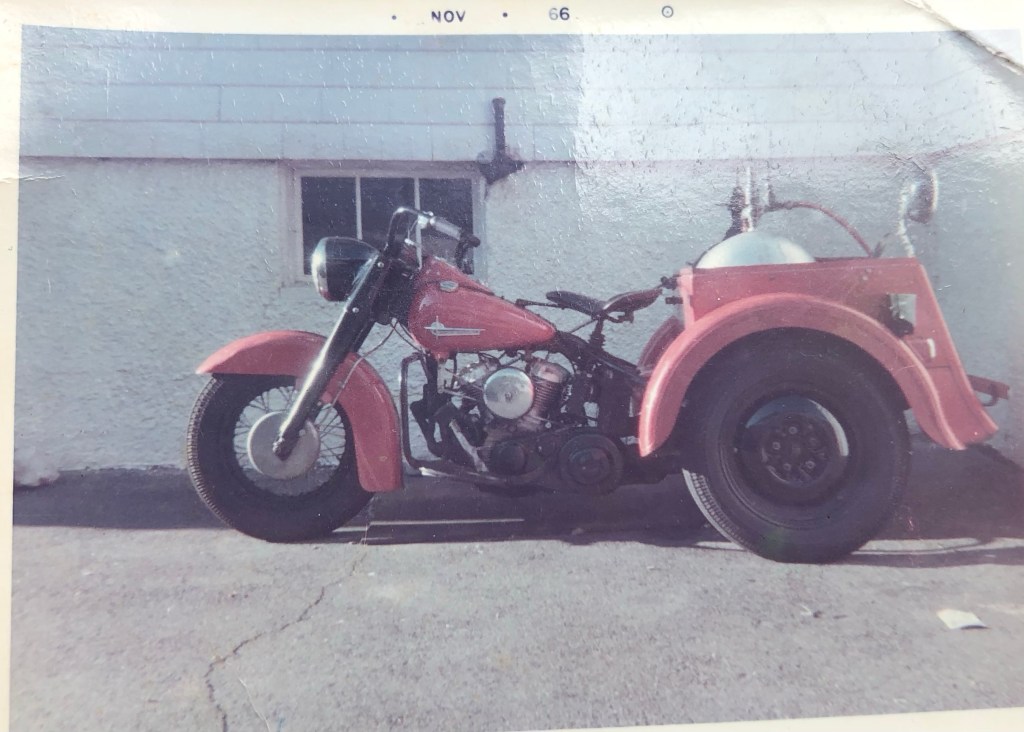

Farless was referring to a fleet of three-wheeled tomato red Harley Davidson Servi Car motorcycles used during summers to spray catch basins in the eleven communities comprising the Project.

The chance visit became a forty-five minute chat that fleshed out the history of state-funded consortium that began in 1948 under the Project’s first superintendent, Robert Armstrong.

The congenial Farless offered me coffee and I relayed my story. As a kid growing up, I used the see the motorcycles traveling through my hometown of Belmont. My friends and I would say, “Boy those bikes are cool!” Little did I realize I would become one of the ‘skeeter killers during the summer of my sophomore year.

That was 1966. I had previously asked one of the bikers how to apply for the job. He suggested I contact Mr. Armstrong. I called him that day and he invited me to the garage.

I was in the proverbial right place at the right time. Another student who’d applied for the motorcycle job had been in a serious automobile accident. Armstrong hired me that day. There were two qualifications: I had to obtain a state license for pesticide applications and change my driver’s license to include motorcycle operations. I quickly obtained the two documents and was ready to work.

Armstrong was an imposing figure, the quintessential Yankee : tall, ramrod thin and patrician.

A graduate of Amherst College, Armstrong became fascinated with entomology. In 1947 he jumped at the opportunity to manage the fledgling organization.

I told Farless the most ironic thing about Armstrong’s physical appearance was his long nose.

“I often remarked that Armstrong, – or ‘Army as he was called- in profile actually resembled his quarry, “ I said. “He had a mosquito nose!”

Farless pulled a Danny Thomas and sprayed his coffee while laughing.

THEN

The crew consisted of five full time employees and the summertime bikers. Armstrong was the entomologist and he divided his time between administrative work and trapping and identifying mosquito species in the field. Much of the Project’s work involved detecting areas of stagnant waters – marshes, estuaries and low lying swamps– and improving drainage, thus ensuing elimination of mosquito breeding areas. Basically, it was a bunch of guys ditch digging in remote wooded areas. Metro west Boston had numerous affluent communities where open spaces were a hotbed of mosquito breeding. On rainy days, the bikers would join the crews.

The motorcycle team, usually three bikers, had the more envious job. We cruised the streets and road on the Servi Cars. Armstrong, an astute innovator, discovered mosquitos also bred in catch basin along all roadways. His genetically primed Yankee ingenuity determined the Servi Car would be the perfect vehicle to deliver insecticide into the basins.

There was storage area behind the bike. He installed a 20 gallon oblong tank inside the vehicle and then attached a pressurized valve and nozzle atop the drum.

Using a compression hose, he attached a six-foot rubber pipe and a pressure trigger similar to spring-loaded garden hose nozzles. At the end of the pipe, Armstrong attached a dispensing tip that would spray liquid in a 360 degree pattern.

Armstrong filled the drum with water and environmentally safe insecticide and inflated it to 100 pounds per square inch of pressure. He squeezed the trigger. A perfectly symmetrical spray burst through the end nozzle. Success.

For decades the Project’s motorcycle crews became a summertime fixture in Metro West. I had a ball during my three summers. It was a fun job. Every rider developed a great tan –from the waist up. Riding through the various communities was educational. When spraying in Cambridge, I always lunched inside the historic Mt. Auburn Cemetery. A sandwich shared with literary greats. We used road atlas maps to navigate through the communities. I learned many short cuts that I came to use even after my employment there ended.

To this day I’ll take routes that perplex my wife.

“Let me guess, we’re taking this shortcut because of the Mosquito Control, right?” she’ll exclaim.

One part of the job was tough: the heat. For seven hours, riders sat astride a 300 pound air-cooled motorcycle engine. Dog-Day August sun plus the engine heat required my drinking a half gallon of water daily. But that was part of the job description. You got used to it. The greatest joy was spraying a basin and watching as a swarm of mosquitos escaped, a certain death awaiting them. Many residents would thank me or give a thumb’s up as I drove along side streets while smoking an Italian cigar. It was satisfying to do part of an effective public health “project”.

Armstrong often lectured the importance of the ongoing battle with mosquitos. And he was correct. Until I’d worked for him I didn’t realize malaria was only one of the dangerous diseases mosquitos transmit (there are about 3,500 species worldwide). This included Dengue Fever and Yellow Fever. West Nile Fever appeared in America after Armstrong retired.

NOW

Bob Armstrong retired in 1977. Brian Farless is the Project’s fourth superintendent. A native Virginian, he majored in environmental studies in college and held such jobs as studying the death of bats in Wyoming and turtle migrations in Colorado. He eventually became interested in insect-borne disease control. He has supervised the Project since 2017.

“They eliminated the motorcycles in 1982,”he said while finishing his coffee. “My predecessors decided to find more environmentally safe insecticides. They also felt the motorcycles were too expensive, too much overhead. We’ve gone from Harley-Davidsons to Schwinn bicycles that were introduced in 2001. The age of the real bikers are gone!”

The Project still hires college students for summertime work. It has a fleet of bicycles. Instead of a spray, they drop synthetic bacteria pellets – called BTI- into the basins that are carried in baskets. They also mark that basins with spray paint to certify the earth-friendly insecticide has been applied.

“One other thing is different,” Farwell said. “The motorcycles were painted bright red. You could really see them and they had lettering on them. Our bicycles have drab colors with no identification. We’ve had too many stolen so we keep as inconspicuous as possible.”

The Project itself is different. In the 1960’s there were eleven participating communities. The number has increased to twenty-seven and now incorporates cities and towns in Suffolk County. In fact, there are now eleven Projects across Massachusetts.

Farwell said another change was the method of distributing insecticide sprays that would cover larger areas. The machines were called “fogging machines” and the process was conducted at night after temperatures cooled. The foggers were extremely loud and produced a fog like cloud. They were effective but noisy. Today the Project uses a mist.

“Yeah, just like the old foggers, the mist machines make a lot of noise,” Farwell said. “But that’s to let neighborhoods know our vehicles are out there.”

As an adjunct to the misting, the Project contracts with a helicopter company that in spring “dusts” the communities with an environmentally friendly insecticide. Farwell said the aerial application covers 1,800 acres.

He said he really enjoys supervising the Project. Although his job is primarily administrative, he, like his predecessor Armstrong, occasionally joins the crew in their wet, swampy “office”.

“One of the occupational hazards is Lyme Tick infestation,” he said. “ Guys leave their work areas and a covered with ticks. It’s a problem.”

Our pleasant conversation ended and I exited from the old, familiar building. I hopped into my car and driving away, the memories of an oh-so-long-ago adventure stayed with me. It pleased me that the continuum was there. The Project was fighting the good fight. The world has changed but mosquitos haven’t. I smiled as I took yet another short cut home. Yes, honey, the Project is still with me.

Loved your story traveling down your memory lane. The adaptations the company has made and still serving the neighborhood safely is remarkable. Thanks for sharing! Really enjoyable!

LikeLike