Why A Hulihee?

By

Leo de Natale

Illustration by Vince Giovannucci

“To shave or not to shave. That is the question!”

By the time a young boy morphs into a teenager, the subject of facial hair, beards, mustaches and any combination of the two have bounced around in his head. Most sons growing up watch their fathers exercise the daily ritual of removing the five o’clock shadow and facing another day.

“Daddy, can I watch you shave?” a 10-year-old son will ask as he becomes fixated on this rite of passage.

“Yes, Johnny, you can,” the father replies. “And remember some day you’ll be doing the same thing.”

The boy watches his dad wash the face, apply the shaving cream – that’s a favorite – and slowly, methodically stroke the cheeks, neck, chin and upper lips. On a rushed day, the father will yelp- ouch! too close and another razor cut. Out comes the coagulating styptic stick that staunches the bleeding. An astringent after shave is then applied with an accompanying “Ahh”. The aroma lingers and the boy files the smell in his olfactory memory bank.

Once in a while adult males will sniff Old Spice, Brut, English Leather, Drakkar Noir or other popular colognes and will be catapulted back to their youth.

Beards and facial hair have existed since the man became homo erectus and lurched out of his cave. Across the millennia – especially dating back to the Greeks and Romans- beards have been an integral part of society. Anthropologists claim in ancient times the hairiness had several purposes.

The beards created evolutionary pressures among tribes to enforce dominance hierarchies. Beards = testosterone and they affected mating habits- the iconic Neanderthal man dragging his female mate by the hair and grunting “Me take you to cave”. Also, it is proposed that among warring tribes, beards were actually useful in reducing the impact of blunt force during tribal battles. Had they lived in that era Giuseppe Garibaldi or Beat poet Allen Ginsberg would have protected themselves well.

In appearance early humans weren’t much different from the rest of the animal kingdom. We were all hairy beasts and evolution shows some things don’t change, especially in various places in the world. You wouldn’t confuse Swedes with Moroccans.

Throughout modern history men’s facial hair has varied as often as hemlines (when women more commonly wore skirts and dresses). Egyptians shaved their faces and scalps although Pharaohs were often depicted with long, well-oiled chin beards. Along came the Greeks where hirsutism was the accepted norm.

In fact, Socrates and his disciples purportedly would play games and watch fleas jump from one beard to another. Simple pleasures for not so simple philosophers. Beards grew and predominated during the Hellenic golden era.

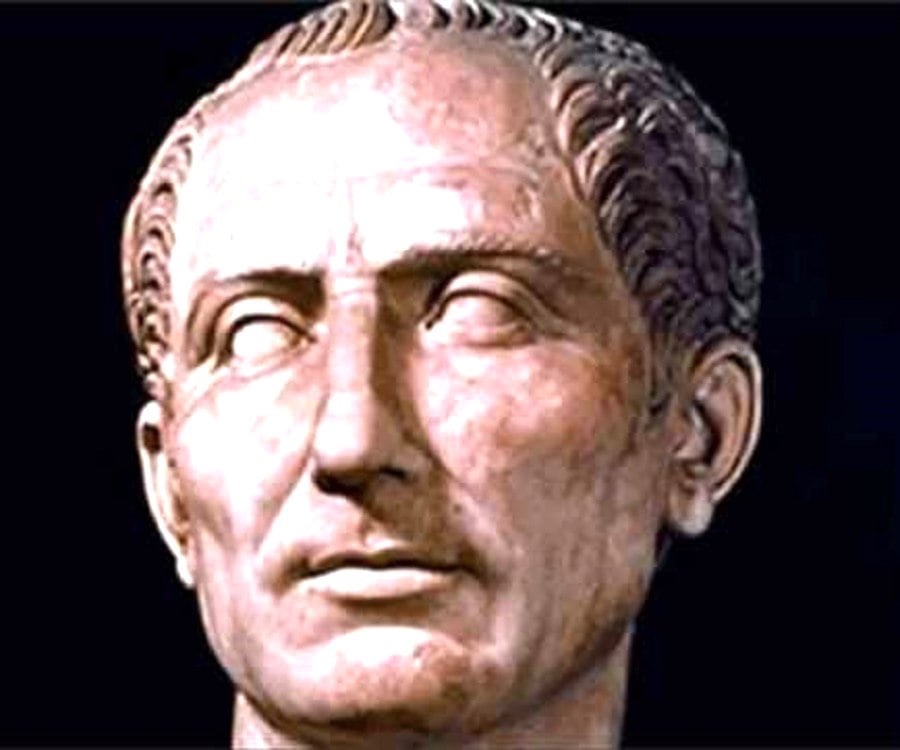

The Romans succeeded the Greeks and theirs was a distinctly anti-beard empire. The emperors were predominantly clean-shaven from Julius Caesar, Augustus, Caligula, Tiberius et al. It is evident in the various sculptures that have been preserved through the ages. The invading Barbarians liquidated the Roman Empire and men’s facial appearances reflected their conquerors’ preferences. The grandeur of Rome morphed into a region of scruffy, bearded, smelly infidels lacking in hygiene and good taste. During the Middle Ages, hirsutism was the European norm. Then Protestantism erupted. There was a clean-shaven Martin Luther and bearded Henry VIII and John Calvin. These gentlemen created a tectonic upheaval in Western history, religion and facial hair.

Regarding beards, the Protestant Reformation created the proverbial line in the sand. During that period, Roman Catholic Church clergy were clean shaven. As a matter of physically making an ecclesiastic statement, Protestants – with the exception of Luther- donned beards. The religious battles with the Church were longstanding and the political positions of European states would follow a centuries-long conflict – rebellious England vs. Defender of the Faith France are a prime examples. Both groups presumed a Michaelangelo-bearded Almighty God was on its side.

Politics and beards aside, many if not most men living between the 16th and 19th Centuries were unshaven. A fundamental question persists regarding the decision: to shave or not shave. And that’s hygiene. Men and women during those times were- shall we say- not terribly clean. European peasants reportedly bathed themselves about three times per year. Washing and bathing were infrequent at best – remember Socrates and his flea-bitten disciples. If men weren’t washing their hair it’s safe to say the beards weren’t earning extra attention and were a safe haven for bacteria, vermin, dirt and last Thursday’s meat loaf. During that era B.O. could mean either body or beard odor.

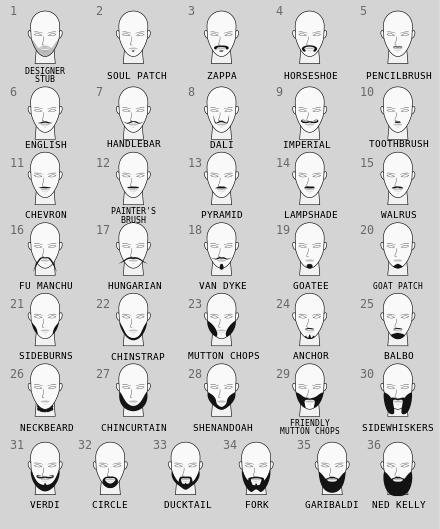

Facial hair history does have an historic timeline but today beards and mustaches provide an even more important contribution: Humor! The laughter begins with the names. Each style has a history and each generation seems to add various alterations. There are more than twenty distinct beard styles with such names as The Garibaldi, Monkey Tail, Friendly Mutton Chops, Verdi and, of course, the Van Dyke.

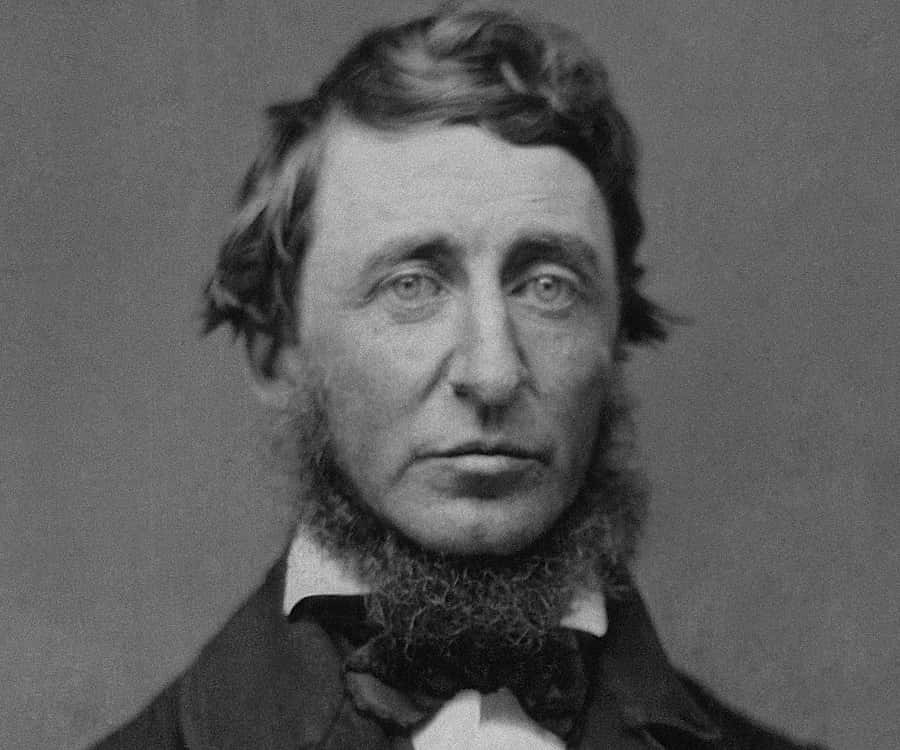

Many famous men have sported beards that become eponymous or create visual memory lasting a lifetime. For example, Transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau was known for his masterpiece book “Walden” and other essays. Thoreau was photographed with a beard style called the “neck beard”. While spending his time building a log cabin on the shore of Walden Pond, Thoreau decided the grow a beard that included only his neck. His face was clean shaven that highlighted his crystal blue eyes. During the 19th Century many strange things occurred in Concord, Massachusetts and Thoreau’s facial hair was one of them.

It’s uncertain if Thoreau was a trendsetter but it turns out New York publisher Horace Greeley also grew a neck beard. German composer Richard “Die Meistersinger” Wagner also followed suit. Henry David was in famous company. Wagner’s contemporary Guiseppe Verdi sported a beard that became associated with the world’s most famous opera masterpieces. From an historic standpoint, maverick Roman Emperor Nero purportedly wore a neck beard.

Facial hair has always had a humorous aspect. Beards and mustaches obviously alter a man’s physical appearance. A white bearded Santa Claus evokes childhood memories of a fictitious character who represents mirth and holiday cheer. Segue to a rock music Frank Zappa whose mustache/goatee combination was so well known that his style has become eponymous. Seeing his facial hair evoke memories of Zappa’s record album Weasels Ripped My Flesh.

One can’t help but laugh at some of the outrageous names attached to beards. At the top of the list are the Mutton Chops and its offspring, the Hulihee and Friendly Hulihee. Also included are the “Claus”, Shenendoah, Old Dutch, ZZ Top, Handlebar Chops, Friendly Chops, Anchor and the Full Spade.

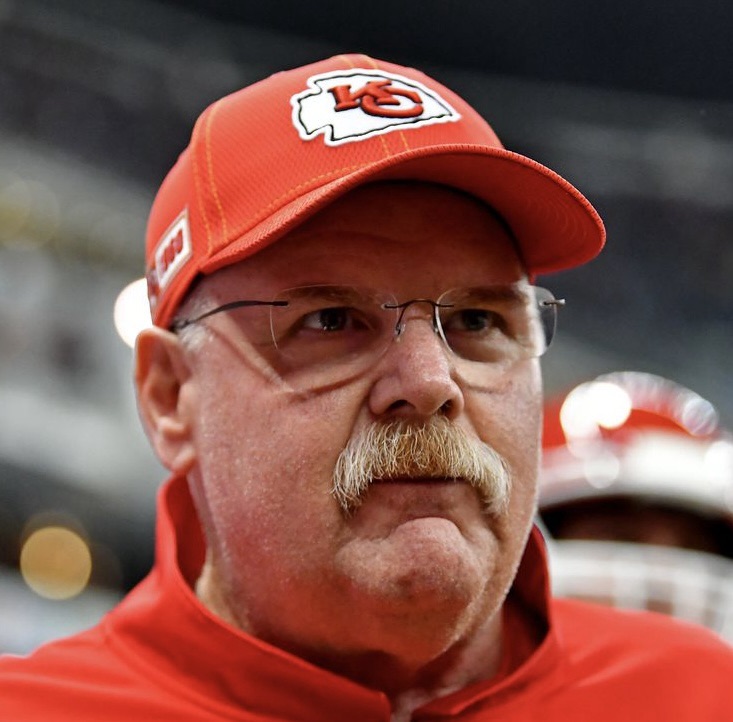

Not to be denied, there are numerous mustache styles, some visually descriptive: Chevron, Lampshade, Painter’s Brush, Pencil – and the Parted Pencil . Others evoke chortles: Walrus (think Kansas City Chiefs coach Andy Reid), Handlebar, English, Hungarian, Dali, Fu Manchu and the Horseshoe. There’s the arcane Imperial Kaiser Wilhelm mustache and a hybrid called the Beardstache.

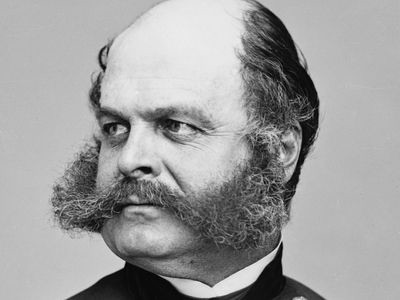

There’s plenty of history with these names. Civil War General Ambrose Burnside – considered the worst Union commander – carved a niche in facial hair history. Gen. Burnside started his career by growing hair adjacent to the ear. He popularized the look that eventually was named “sideburns”, a style contemporarily popularized by Elvis Presley. Of course Burnside wasn’t finished. His facial hair eventually morphed into another signature style: Friendly Mutton Chops. No one ever took Gen. Burnside or his beard seriously.

Noted Harvard trained paleontologist Dr. Keith Vitalis has dedicated his life to tracing the long hairy history of man’s obsession with beards and mustaches.

“Men have a schizoid approach to mustaches and beards,” he said. “We either love them or hate them, myself included.”

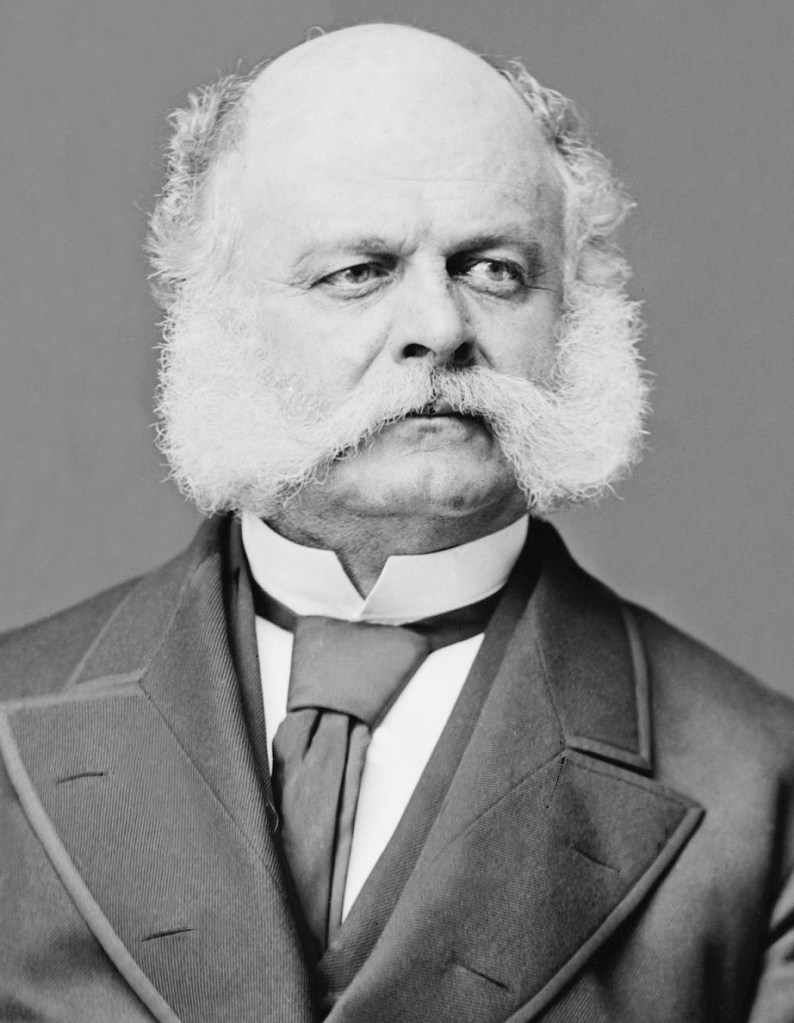

Vitalis speaks from experience. He long ago decided to adopt a Janus-like appearance: he shaves only the right side of his face. The left side has a bearded appearance resembling the full beard Garibaldi!

“I do it for effect,” he said. “Some men love their facial hair; others are psychologically confused. For example, young men regard beards and mustaches as a rite of passage. Growing facial hair states ‘I am a man!’”.

According to Vitalis, facial hair has psychological associations. Men with weak chins or who have poor self images while shaved will hide behind a curtain of hair. Other men try to make a social statement. Today’s rock musicians are often bearded and express a counter-culture appearance while becoming millionaires with their musical success.

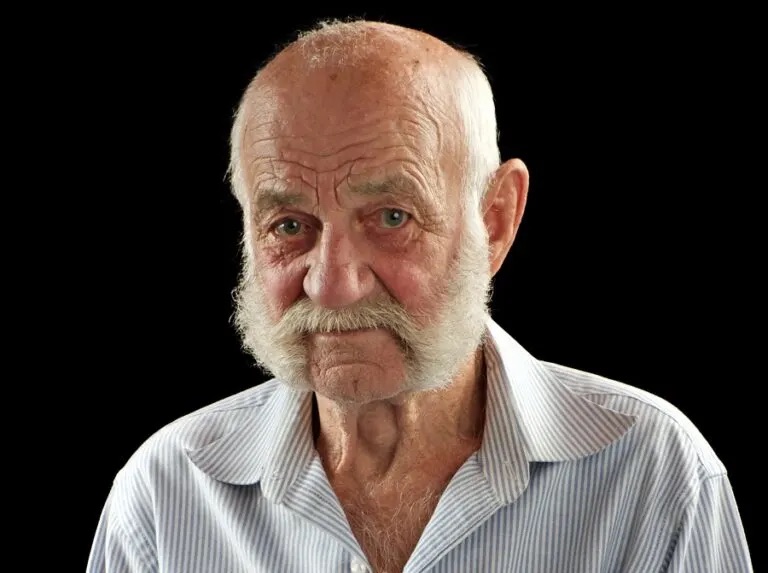

What about old men who often sport a white mustache and/or beard?

“Some men think growing a graying mustache/beard gives them an avuncular or perhaps patriarchal appearance,” Vitalis said. In reality many of these men are hiding behind a wizened mask. Older men with beards think the grey hair hides aging skin or a sagging gullet – the bain of all elderly men and women. A 73-year-old man with a gray beard is simply calling attention to his chronological age. Can you take any man seriously if he’s wearing a white Fu Manchu?, Vitalis asks.

Hairy faces have been with mankind since the dawn of time. In this era of computers, software and apps there is still room for fun. Two ingenious apps, Beardify and Stachify, allow a man to create virtual and instant beards and mustaches. One moment you’re Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox or Moses parting the Red Sea. All in the flick of a finger on a cell phone. You can even transform women’s photos into a band of bearded ladies. The laughter created by facial hair never ends. It grows and grows and grows.

****************************************************************************************

This is my blog essay number 60. What started out four years ago as a diversion from the Covid 19 nightmare became a reinvigorated passion to write. I’ve had fun stringing together essays and poems. I want to thank my wife Kathy who’s been supportive in my endeavors. She’s also my editor extraordinaire. Thanks also to my dear close friend, optometry school classmate and colleague Vince Giovannucci whose artwork and cartoons have added such zest and humor to my essays.