Caravaggio’s Son

By

Leo de Natale

Illustrations by Vince Giovannucci

Some people have an obsession with colors. There are many women who have a thing about purple. They dress in purple, their homes are fifty shades of purple – sofas, wall paper, bathroom tiles. Others prefer pink or orange. A certain Rhode Island gentleman, however, chose a different hue.

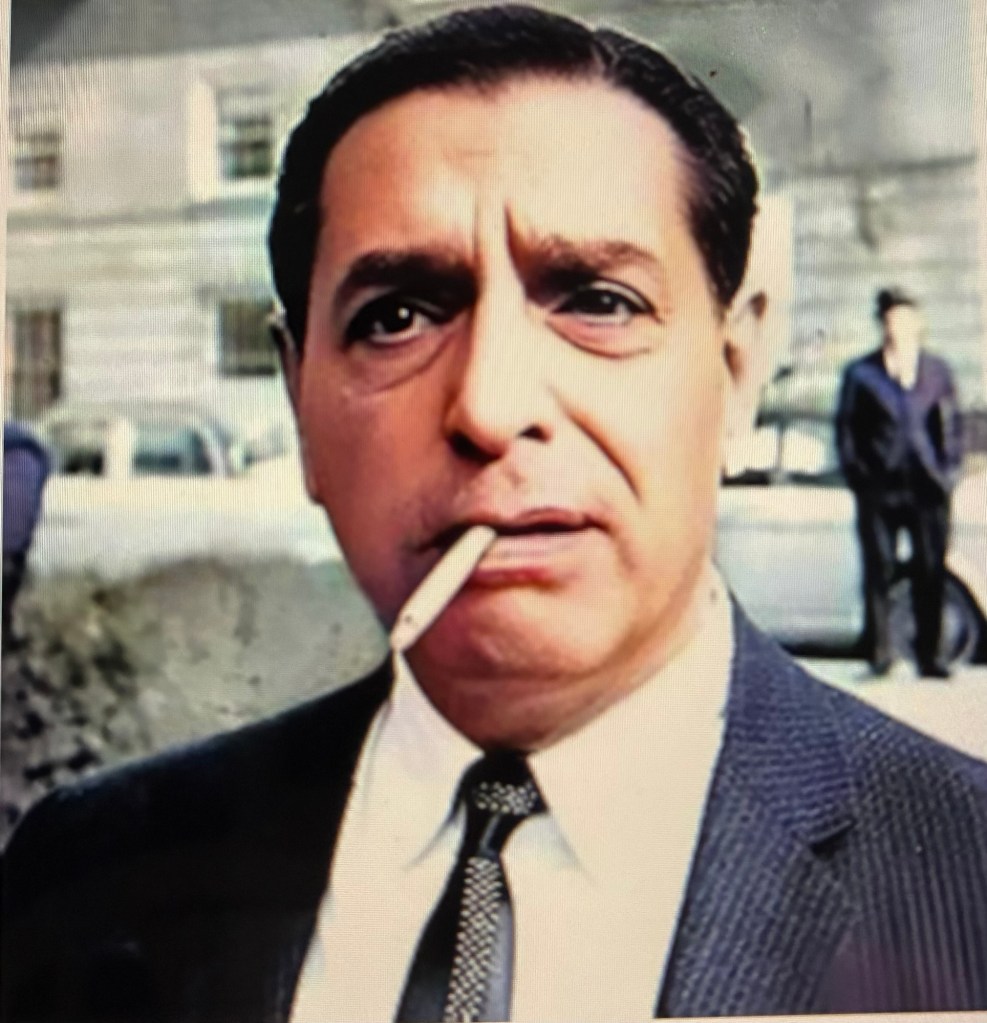

No one is really sure why or at what point in his life Arthur Di Nobili fell in love with the color black, especially black clothing. His usual monochromatic attire consisted of black shoes and socks, black polyester slacks that crackled with static electricity in wintertime and black or sometime gray acetate shirts. His left ring finger was adorned with a massive gold-and-onyx ring bearing the profile of a Roman Centurion. Such apparel accentuated his swarthy southern Italian features that naturally included a black mustache.

In 1977, Arthur attended Princeton University, on full scholarship (he achieved three 800s on his SAT scores). He was known at Princeton as the “Italian Johnny Cash”. He created an avalanche of sardonic laughter the day he wore to class his infamous black disco shirt festooned with hordes of scarlet parrots perched upon palm branches.

He was indeed a walking contradiction. His outward appearance conveyed Providence Goombah — he was born in the Rhode Island city. A virile six-footer, Arthur was the possessor of smooth, olive-toned skin. His beard was so coarse, his friends teased, he could wake at 4:30 in the morning and have five o’clock shadow thirty minutes later. Arthur Di Nobili’s eyes were a deep penetrating umber and when, as he was so often, excited, his eyes would become bulged by the exposed white sclera as his eyelids retracted with emotion. He also had the habit of voluntarily raising his eyebrow as a menacing emphasis. His voice was deep and sonorous.

Arthur was blessed with an IQ of 150 and relished such varied subjects as quantum physics, the Hegelian dialectic or Hittite pottery. He was engrossed with Baroque art and his favorite painter from that era was Caravaggio, the master of chiaroscuro.

His college dormitory cronies became enamored with Arthur’s engaging personality. He would regale them with such utterances as, “Look, all I care about is Nietzsche and getting laid.” As the only child of divorced parents, he extolled the virtues of marriage, yet boasted of his womanizing during visits to New York City.

The crusty aristocrats of Princeton never knew quite what to make of this multifaceted personality. He confounded them with his intellect (he was one of few to graduate with a straight 4.0 average). He had the uncanny ability to maximize the efficiency of his waking hours.

For example, during his junior year Arthur was simultaneously on the dean’s list, co-captain of the varsity soccer team, president of the Dante Alighieri debating society and a member of the university’s a capella choir.

Perhaps the most unusual of Arthur’s many idiosyncracies was his obsession with the Mafia. Although neither he nor his family had underworld ties, everyone presumed he did because of his encyclopedic knowledge of what Arthur referred to as “America’s sub rosa General Motors”. For years, his daily routine was to purchase four morning newspapers: the New York Times, the New York Post, Providence Journal, and the Washington Post. He would assiduously scan these for underworld news items- this was pre-internet. On his dormitory room wall he had drawn an elaborate and astonishingly detailed flow chart of the Mafia, complete with every chieftain’s name, moniker, place of birth, city of operation and the rackets therein controlled.

Once in New York City, Arthur and his Italo-American classmate, Nick Volterra, a Type A personality from Westchester County, spent several hours in a Manhattan South police precinct for what Volterra called a case of mistaken identity. According to Nick (whom Arthur dubbed “Travis Bickle” for his resemblance to actor Robert Di Niro’s character in the movie Taxi Drive), the two spent a winter’s weekend in New York after a Princeton-Columbia basketball game.

“Arthur would always ‘dress up’ for a trip to New York,” Nick recalled. “He had this big, gray homburg hat he’d bought at the same haberdashery where Mafia don Carlo Gambino shopped. He was wearing his black Chesterfield coat and carrying that damned Samsonite brief case . Sometimes it contained only a sandwich but he liked taking it along for the “effect’” and I would say, ‘What no violin case?’”.

“Anyway, we’re on a bus on the West Side, and Arthur’s there telling me about the latest “hits” by the New York mob,” Nick said. “He always got excited talking about that sort of thing, and his eyes got really beady and intense. He was talking about the demise of a minor hood named Mario “The Nose”Granito. He’d say ‘Yeah he was horning in on the Gambino’s loan sharking. They garroted the son-of-a-bitch and stuffed him into a pink Cadillac. A pink Caddy, that’s a sign of real disrespect. The Nose was a fag anyways. He had no balls.’”

Volterra said he became uneasy as he noticed two women in front of them exchanging fearful glances. Suddenly, one of the women (it turned out they were Bellevue Hospital outpatients) yelled hysterically, “Murderers! Murderers! We’re going to be killed.”

The bus driver pulled to a halt and tried to calm the women while Arthur, obviously enjoying the ruse, glared with those eyes and, as an emphatic gesture, grabbed his groin and shouted, “Hey right here’s your murderers, you scumbags!!!”

Three hours later, after undergoing interrogation at Manhattan’s Precint 4, Arthur and Volterra were released. The police had questioned Arthur but discovered his identification. Arthur gladly opened his brief case and displayed its contents: a jar of Skippy Peanut Butter, three changes of underwear and his four newspapers.

By his senior year, Arthur had decided to pursue a career in health care. It was a tossup between dentistry and medicine. He opted for medical school because he told friends he didn’t care for spending eight hours a day sticking his fingers into somebody’s mouth. At Harvard Medical School, Arthur quickly established himself as the class eccentric. No one could prove it but he was strongly suspected as the culprit who dressed an anatomy cadaver in monk’s robes, complete with a Chianti bottle in the corpse’s right hand and a lit cigar between the teeth of the body’s grizzled, formaldehyde-awashed face.

It was also at Harvard that Arthur was “thunderstruck”, as he put it, by Lori Johannsen, a first year classmate from Minnesota. If Arthur was polyester, Lori was crepe de chine; he was Mediterranean terra cotta, she was Scandinavian cut glass. Their often stormy relationship became a classic example of oil and vinegar, noir et blanche. Light and shadow, just like the chiaroscuro paintings of Caravaggio, a major proponent of this technique and most often associated with a dramatic use of lighting.

Lori was at first glance a striking female. She was tall, blonde, and blue-eyed. She had an athlete’s lithe physique that developed from years as a varsity swimmer; her skin was alabaster-toned. Arthur referred to her as his “Venus reincarnate”; others saw her as a flat-chested, weak-chinned hypochondriac who once told a fellow student she skipped classes because she thought her blood pressure would be elevated that day. She could divine a common cold two weeks in advance.

And for all Arthur’s sexual braggadocio, in actuality he reflected conservative attitudes of a second-generation Italo-American. He could be and often was promiscuous with a coed here, or a comely graduate student there. But Arthur had this Godfatheresque fantasy regarding the purity of womanhood he saw in Lori. At times he fancied himself a latter-day Michael Corleone, the literary and intellectual Mafia character.

And so the relationship evolved, or regressed. It was during the summer between third and fourth year of medical school that an event occurred that drastically altered Arthur’s life. During summer break, Arthur and an old neighborhood friend, George “The Greek” Scatopolous, spent two weeks driving cross country to visit Lori and her family in rural Minnesota. The two city slickers likened it to an urban Meriwether and Lewis expedition to the Northwest Passage.

For the first three years of medical school, the romance between Arthur and Lori ebbed and flowed. It was a melodrama reminiscent of the old dime store novels. She would harangue him over the rigidity with which he dearly held the Providence/Italian/Macho ethic.

“You’re as progressive as one of your grandmother’s zucchinis,” Lori yelled at him during one of their innumerable fights.

“Yeah well at least I take my clothes off at night,” he retorted, referring her distaste for nudity. “Your problem is you’ve always worn tight underwear!”

Arthur arrived at the Johannsen home tired, hot and incredibly drunk on chianti. A predictably ugly scene ensued at Lori’s doorstep. Words were exchanged with Lori’s livid father. Arthur and “The Greek”, sped off towards Minneapolis via Interstate 84. A thunderstorm with high winds blew out over the Minnesota flatlands. Rain cascaded in sheets off the lightweight Chevrolet they were driving.

Arthur could not recall precisely how it happened but a tractor-trailer containing 30 tons of feed corn jackknifed, swerved towards their car and sent it careening into a drainage ditch thirty feet away from the highway.

Nick was killed instantly as the car roof collapsed and crushed his cervical vertebrae. Arthur was discovered outside the wreckage and was unconscious.

For nearly a month he lay in coma at a Minneapolis hospital. Lori visited once and spent the remainder of the summer horseback riding near her home. She never saw him again.

After Labor Day Arthur was transported to Providence and, as if by the influence of some magical elixir wafting through the city’s atmosphere, regained consciousness by September’s end. The recovery, unfortunately, was incomplete. Arthur was blind. The neuro-ophthalmologist at Providence Hospital told Arthur and his anxious mother he had sustained significant trauma to the base of his skull called the occipital area, the location of visual processing. The doctor said his sight might be restored within weeks or months but he might never again see the skyline of the Rhode Island city he called home.

Arthur showed remarkable resilience. “At least my world is colored black” he quipped with gallows humor. But alone at night, and surrounded by internal and external darkness, despondency oozed through the crevices of his battered mind: “I’ll never see another Princeton-Harvard game,” he thought. “I’ll never see another St. Anthony’s feast in Little Italy…………I’ll never watch Frank Sinatra sing again.”

Three days before his release from the hospital, a rush of noise entered his room. He heard muffled voices and the air became heavy with the smell of sweet cologne and smoke from an expensive cigar. As Arthur lay there, a large warm hand gripped his. A man’s soft voice asked,

“Arthur, my son, how are you?”

Arthur recognized the voice and immediately associated the face he’d seen at numerous Senate sub-committee hearings. It was Raymond Patriarca, capo of the Providence mob. “Il Padrone” was a typical Mafia don: wanted and hated by state and federal law enforcement but revered by the Rhode Island Italian community. He was, in their eyes, a modern day Robin Hood with garlic and prosciutto.

“Arthur, you have made us very proud in the past,” Patriarca said in a lilting, paternal tone with an unmistakable Italian accent. “You have brought honor to this neighborhood. You have gone to the best schools, achieved things that I hoped my own sons would achieve. I want to help.”

As Arthur listened in near disbelief over the visitor now sitting beside him, Patriarca told him all his medical expenses would be paid. Any rehabilitation or vocational training would also be subsidized. This was the same Raymond Patriarca that two days prior had ordered an execution of Eugenio “The Tomato” Innocenti because of attempted burglary of his daughter’s summer home and the theft of three hundred pounds of provolone cheese from Patriarca’s underworld headquarters in North Providence.

Patriarca was good to his word. The bills were paid. He provided Arthur with a comfortable apartment near his mother’s home. He paid for nursing until Arthur could fend for himself.

It was at this juncture that Arthur experienced an artistic influence that shunted him along a different path. As a child, his grandfather had taught him to play the mandolin, a stringed instrument that accompanies the Italian soul. He had outgrown the interest for such an instrument but suddenly, in the dark world he existed, he took pursued even greater exponent of the heart – the violin.

Jacob Cohen, a former virtuoso fallen on hard times, was discreetly contacted by Patriarca intermediaries. He had once been concertmaster with the New York Philharmonic but a sour marriage, a few sex scandals and his penchant for high living contributed to his downfall. Cohen was now earning money by existing in a musician’s purgatory: tutoring would-be Paganinis. Cohen admits today that mentoring Arthur was perhaps the salvation of his checkered career. The publicity he later received, locally and internationally, catapulted him once again to prominence.

Working with Arthur was originally trying. They traded ethnic slurs but after the initial feeling-out period, Cohen (referred to as a kosher Ichabod Crane, both in temperament and appearance) discovered the latent artist in Arthur. Teaching a blind man to play violin, he would say, was simultaneously difficult and easy. It was difficult because the musical notation had to be put into more abstract form; easy because the blind man’s remaining senses made Arthur more aware of the nuances of music.

The two men came to understand each other to such a degree they combined their talents. They began playing duets and appeared at weddings, Bar Mitzvahs and musical events around Providence and throughout New England.

Nearly three years to the day after that fateful evening in Minnesota, a miracle occurred. Arthur was preparing for a concert before the Providence Jaycees when the sensation, the suggestion of light from an ancient, wooden bulkhead, appeared in the midst of his consciousness. The light sprung forward, first slowly but then with greater rapidity, blur piled upon blur. Gross forms were becoming discernible. Vision was coming back. He could see!

The news splashed onto local newspapers and television stations. The national media learned of the blind, Princeton-educated violinist re-entering the world of light and images. There were tears of joy.

Five years later, Arthur Di Nobili stood tall inside Providence’s Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral. He wore black again but the black polyester was no longer an empty expression of poor taste in clothing. It was symbolic of the world into which he had been submerged. Dressed in black, he played Mozart’s The Requiem at Raymond Patriarca’s funeral mass. A thousand eyes cried.